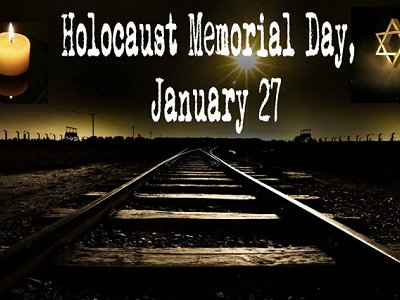

HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL DAY

Genocide is almost unbearably hard to think about, but it gives us a reality check on the fatal weakness of human beings to manipulation by others:

Holocaust Memorial Day landed on January 27 because this was the day in 1945 when the Soviet Army liberated the Auschwitz concentration camp. This country has marked Holocaust Memorial Day for only the last eight years. This seems odd, given the Holocaust happened over sixty years ago, but the post-war European continent was dominated by a struggle to survive and a yearning to forget which helped to suppress talk of the shocking cruelty which so-called civilised Christian nations could inflict on minorities in the right conditions. There was another motivation in the creation of Holocaust Memorial Day, for crimes of genocide have suddenly become fashionable. In the last seventeen years they have been visited on at least five different peoples: Iraqi Kurds, Bosnian Muslims, Kosovar Albanians, Rwandan Tutsis and the Fur Sudanese. Without visual symbols and rituals of remembrance, the human memory tends towards forgetfulness, which can soon lead to complacency and finally indifference.

The Jewish Holocaust has posed profoundly disturbing questions for both Jewish and Christian communities. At its heart lies a paradox which the Church cannot ignore but which we know we cannot solve: if we believe in a God who is all-powerful and all-loving why did he allow evil on a previously unimagined scale to be perpetrated without intervention? It is difficult to say anything meaningful in the face of such horror without feeling like you are resorting to cliché. If something shakes what we believe about God, the temptation is to suppress any thought of it, in case it challenges what we hold most dear in life. But there are important things which should be said. One is that, by deduction, if God exists and his character is all-loving and all-powerful, then he must value human freedom most deeply, not to have intervened. This poses a problem for God also, because many use their freedom to abuse the vulnerable of this world, the very people God says he chooses to privilege.

The other truth we should always adhere to is that God has moved decisively in this world, in the life of his Son, who was deliberately exposed to the worst kind of death as God’s way of delivering the world one day from the sin with which it offends him and ruins itself.

This is the truth we call to remembrance every week at church in bread and wine. We look back with gratitude: Christ has died, and we forward in hope: Christ will come again. Yet if you share this with a Jewish Holocaust survivor you may find the words drying up in your throat.

The concentration camps were predicated on a history of European anti-semitism which saw Jews as responsible for the death of God’s Son and so worthy of contempt as Christ killers. This virulent strain of thinking can sadly be traced, in different potencies, from the earliest Church theologians, through Martin Luther and influential nineteenth century German theologians, to Hitler himself. So for a Jewish person, there is every chance they will see our remembrance of the death of Christ as the source of much of their grief. I am glad to say, nevertheless, that great strides have been made in recent decades between the two faith communities. In this country, the Council of Christians and Jews has quietly done sterling work to deal creatively with differences and disagreements, while the recently deceased Pope John Paul II worked tirelessly and with great integrity to deal with the contemptible anti-semitism which has poisoned Roman Catholic communities in Eastern Europe for generations.

Holocaust Memorial Day poses political dilemmas as well as spiritual ones. The usual rhetoric people employ is ‘never again’, which is an utterly meaningless response unless we are willing to send soldiers to die in far away places in disputes few people understand well. In 1994, as the genocide in Rwanda began to unfold, officials in the State Department in Washington had a problem: they wanted to know, were the rival tribes Hutu and Tutsi, or Tutu and Hutsi? They had to ring a professor of African studies at Harvard to get an answer to that question. If America’s finest officials didn’t know, what chance did the rest of the population have? People find it hard to care when they don’t really understand. In a hundred days over 800,000 people were slaughtered with machetes.

It was the wars in the Balkans which eventually gave rise to a short-lived concept of humanitarian warfare, whose title even its supporters admit is an inherent contradiction. Humanitarian warfare was a call for nations to intervene in the affairs of sovereign nations without the need for U.N. sanction where minorities were being systematically killed or relocated. It was employed to justify armed intervention in Sierra Leone and over Kosovo. It was then cited, among other more prominent reasons, as a basis for the invasion in Iraq, from which it has received a crippling blow.

And so the words ‘never again’ trip too easily from human tongues. There is every chance that crimes of genocide will happen again and again as the global population soars, as people start to fight over natural resources like water and climate change affects the viability of previously settled communities.

Studies of genocide are almost unbearably hard to see out, but they remind us of the sheer scale of human sin and the fatal weakness of human beings to manipulation by others. People make blithe assumptions about the savagery of other communities and the civility of their own without appreciating the inherent vulnerability of all societies mired in sin. I doubt Germans thought they were capable of such savagery once; I suspect many still can’t quite believe they were. It may be hard to take useful lessons from a commemoration as dark as this, but at the heart of it is a community’s treatment of minority ethnic groups. In biblical times such people were called ‘the alien’ and biblical law spoke powerfully of the need to protect the alien from abuse, to give him or her equal status under the law and to act hospitably towards them. By the same token, the alien had to exercise new responsibilities and was encouraged to embrace the culture and identity of the host nation.

We are encountering an unprecedented level of immigration in the U.K. today, where there are powerful temptations to caricature certain minority ethnic groups without differentiation. At the same time, some freshly arriving immigrants are faced with an entirely new temptation: that of living in a digital bubble, where contact with the native population is limited and their only media sources are obtained by satellite dish from another culture. Neither temptation, among others, helps us to deal with important questions of integration. There are vital debates to be had about citizenship today. In drawing up its own constitution, the European Union explicitly left out any reference to the Christian heritage of the continent, and there are those who would deny that Christianity has any historic role in shaping the culture and politics of this country also. Despite these assertions, I believe that the better we understand our Christian heritage as a lively and informative tradition, the more assured and civilised we will be in dealing with the so-called alien in our midst.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?